Lab 1 - Force Table

Introduction

All measurable quantities can be classified as either a scalar or a vector. A scalar has only magnitude while a vector has both magnitude and direction. Examples of scalar quantities are the number of students in a class, the mass of an object, or the speed of an object, to name a few. Velocity, force, and acceleration are examples of vector quantities. The statement "a car is traveling at 60 mph" tells us how fast the car is traveling but not the direction in which it is traveling. In this case, we know the speed of the car to be 60 mph. On the other hand, the statement "a car traveling at 60 mph due east" gives us not only the speed of the car but also the direction. In this case the velocity of the car is 60 mph due east and this is a vector quantity. Unlike scalar quantities that are added arithmetically, addition of vector quantities involves both magnitude and direction. In this lab we will use a force table to determine the resultant of two or more force vectors and learn to add vectors using graphical as well as analytical methods.Discussion of Principles

Vector Representation

As mentioned above, a vector quantity has both magnitude and direction. A vector is usually represented by an arrow, where the direction of the arrow represents the direction of the vector, and the length of the arrow represents the magnitude of the vector. In three-dimensions, a vector directed out of the page (or along the positive z-axis) is represented by (a circle with a dot inside it) and a vector directed into the page (or along the negative z-axis) is represented by

(a circle with a dot inside it) and a vector directed into the page (or along the negative z-axis) is represented by  (a circle with an × inside it).

In mathematical equations a vector is represented as

(a circle with an × inside it).

In mathematical equations a vector is represented as A

. In some textbooks a vector is represented by a bold face letter A.

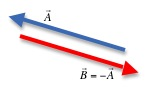

The negative of a vector

A

is a vector of the same length but with a direction opposite to that of

A

. See Fig. 1 below.

Figure 1: Vectors as arrows

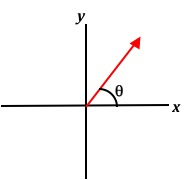

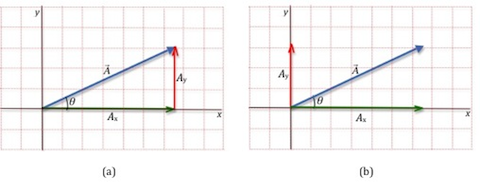

Figure 2: Graphical representation of a vector

Components of Vectors

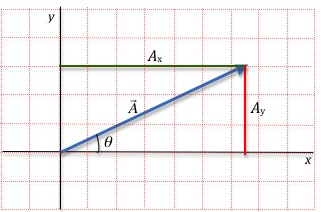

An important technique when working with vectors mathematically is to break them down into their x and y components. In this example, we will consider the position vectorA

directed at an angle of 30° from the +x-axis and having a magnitude of 8.0 miles. From the head of the vector draw a line perpendicular to the x-axis and a second line perpendicular to the y-axis. We refer to these lines as the projections of the vector on to the x- and y-axes. The projection of the vector on to the y-axis gives the magnitude of the x-component of the vector (green line in Fig. 3 below) and the projection of the vector on the x-axis gives the magnitude of the y-component (red line in Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Breaking a vector into x and y components

Figure 4: Representing components of a vector

Ay

is drawn along the y-axis.

Finding components given the magnitude and direction of the vector

We know the direction of theAx

and Ay

vectors, but to find their magnitudes we need to use some trigonometric identities. In Fig. 5 the hypotenuse represents the magnitude of the vector A

and the other two sides of the right triangle represent the x and y components of the vector

A

.

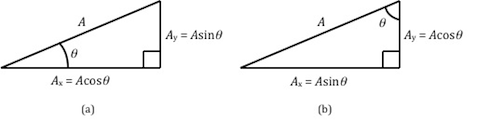

Figure 5: Finding the components of a vector

( 1 )

cos θ =

| adjacent side |

| hypotenuse |

( 2 )

sin θ =

| opposite side |

| hypotenuse |

cos θ =

and (2)| adjacent side |

| hypotenuse |

sin θ =

, we have

| opposite side |

| hypotenuse |

( 3 )

cos θ =

or Ax = A cos θ

| Ax |

| A |

( 4 )

sin θ =

or Ay = A sin θ

| Ay |

| A |

( 5 )

sin θ =

or Ax = A sin θ

| Ax |

| A |

( 6 )

cos θ =

or Ay = A cos θ

| Ay |

| A |

Ax

is always the cosine component and Ay

is always the sine component. However, this will depend on which of the two angles in the right triangle is defined as θ. Note that Ax

is adjacent to the angle θ in Fig. 5a, while in Fig. 5b Ay

is adjacent to the angle θ.

In Fig. 3, the magnitude of A

is 8.0 miles and its direction is 30° above the +x-axis. So you find the magnitude of

Ax

and Ay

as follows:

( 7 )

Ax = A cos θ = 8.0 miles * cos(30°) = 6.9 miles

( 8 )

Ay = A sin θ = 8.0 miles * sin(30°) = 4 miles

Finding the magnitude and direction of the vector from the components

If you do not know the magnitude or direction of the vector, but know the distances traveled in the x and y directions, you can use the Pythagorean theorem to find the hypotenuse, which is the total distance traveled.( 9 )

A2 = Ax2 + Ay2 or A =

| Ax2 + Ay2 |

( 10 )

θ = sin−1

|

| Ay |

| A |

|

( 11 )

θ = cos−1

|

| Ax |

| A |

|

( 12 )

θ = tan−1

|

| Ay |

| Ax |

|

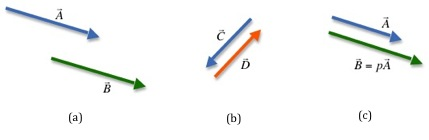

Some Basic Properties of Vectors

Two vectors are equal if they have the same magnitude and direction. So, on paper, you can slide a vector to a different location, but as long as you keep the same length and orientation for the arrow, the two vectors will be equal. In Fig. 6a the two vectorsA

and

B

have the same length and orientation.

The negative of a vector has the same length but with the direction reversed, as shown in Fig. 6b.

A vector multiplied by a scalar will be a vector in the same direction as the original vector but with a different magnitude. In Fig. 6c p is a scalar. The vector

B

has the same direction as

A

but it is longer by a factor of p with p greater than 1. If p was less than 1, then

B

would be shorter than

A

.

Figure 6: Vector properties

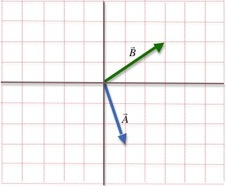

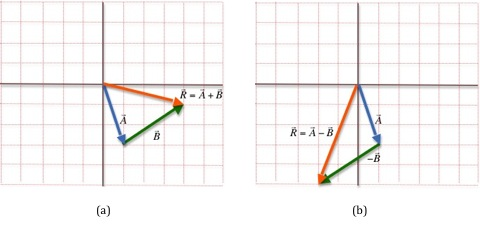

Graphical Method of Adding Vectors

Consider two vectorsA

and

B

oriented as shown in Fig 7. We would like to find the sum and difference of the two vectors. Unlike adding scalar quantities, in this case we need to consider both magnitude and direction.

Figure 7: Two vectors

B

is moved so that its tail is at the head of

A

. Note that the direction of

B

does not change. The red arrow gives the sum

R = A

= A + B

+ B

. Addition is commutative, so you will get the same result by moving  = A

= A + B

+ B

A

to the head of

B

.

To find the difference of two vectors, we can take the negative of the second vector and add it to the first vector following the steps described above for addition. In other words,

A − B

− B = A

= A + (−B

+ (−B )

)

. This is illustrated in Fig. 8b.

− B

− B = A

= A + (−B

+ (−B )

)

Figure 8: Sum and difference of two vectors

Analytical Method of Adding Vectors

Addition or subtraction of vectors involves breaking up the vectors into its components and then performing the addition or subtraction to the x and y components separately.( 13 )

Rx = Ax + Bx

( 14 )

Ry = Ay + By

A2 = Ax2 + Ay2 or A =

and (12) | Ax2 + Ay2 |

θ = tan−1

we can find the magnitude and direction of the resultant vector  |

| Ay |

| Ax |

|

R

. This process will be the same if you are adding more than two vectors or subtracting vectors.

In Fig. 5a,

Ax = 1

and Bx = 3

giving Ax

+ Bx = 4;

Ay = −3

and By = 2

giving Ay + By = −1.

These values agree with the x and y components of the red arrow in Fig. 5a.

In the case of subtraction Ax − Bx = −2; Ay − By = −5

. These values agree with the x and y components of the red arrow in Fig. 5b.

Force vectors

In this lab you will deal with force vectors. In addition to the general properties of vectors discussed thus far in this lab, the following definitions will be useful as you work through this lab. The vector sum of two or more forces is the resultant. The resultant can, in effect, replace the individual vectors. The equilibrant of a set of forces is the force needed to keep the system in equilibrium. It is equal and opposite to the resultant of the set of forces.Objective

The objective of this experiment is to find the equilibrant of one or more known forces using a force table and compare the results to that obtained by analytical method.Equipment

- Force table

- Ruler

- Strings

- Weight hangers

- Assorted weights

- Bubble level

Procedure

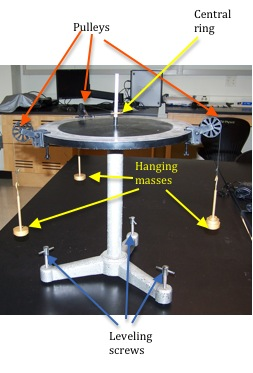

Given two force vectors you will determine the third force that will produce equilibrium in the system. This third force is known as the equilibrant and it will be equal and opposite to the resultant of the two known forces. You will use a force table as shown in Fig. 9, and work with force vectors. The force table is a circular platform mounted on a tripod stand. The three legs of the tripod have adjustable screws that can be used to level the circular platform. The circular platform has angle markings, in degrees, on its surface. Two or more pulleys can be clamped at any location along the edge of the platform. In this lab we will use three pulleys. Three strings are attached to a central ring and then each string is passed over a pulley. Masses are added to the other end of the strings.

Figure 9: Force table

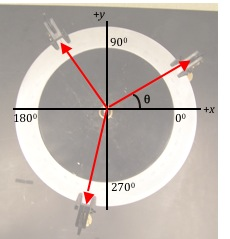

Figure 10: Force table with axes

Procedure A: Finding the Equilibrant of Two Known Forces

1

Use the bubble level to check if the circular platform is horizontal. Use the leveling screws, if necessary, to make the necessary adjustments.

2

You are given two 150 g masses that are to be placed at 60° and 300°.

Remember that the weight hangers have a mass of 50 g each and this needs to be included as part of the hanging mass.

You will determine the magnitude (in newtons) and angle of the third force needed to balance the forces due to these two masses.

3

Represent these forces as vectors on the diagram in the worksheet. Be sure to include the axes.

Each vector in the diagram should be drawn so that the larger the vector the bigger the force it represents.

4

Calculate the x and y components (to the nearest thousandth of a newton) and enter these values in Data Table 1 on the worksheet.

5

Find the x and y components of the resultant of the two vectors and enter these values in Data Table 1 on the worksheet.

6

Now calculate the x and y components of the equilibrant of these two vectors and enter these values on the worksheet.

7

Using Eqs. (9)A2 = Ax2 + Ay2 or A =

and (12) | Ax2 + Ay2 |

θ = tan−1

calculate the magnitude and angle of the equilibrant. Enter these values on the worksheet. These are the calculated value of the third force.

|

| Ay |

| Ax |

|

8

Add this vector to your diagram to represent the third force.

9

Position the third string at the angle you determined in step 6 and hang the mass (including the hanger mass) corresponding to the calculated third force to represent the third force.

Make adjustments (if needed) to the mass and the angle until the ring is at the center. Record this value on the worksheet.

10

Compare the calculated and experimental values for the third force by computing the percent difference between the two values. See Appendix B.

11

Compare the calculated and experimental values of the angle for the third force by computing the percent difference between the two angle values.

Checkpoint 1:

Ask your TA to check your diagram, calculations and the set-up on the force table.

Ask your TA to check your diagram, calculations and the set-up on the force table.

Procedure B: Determining the Placement of Two Unknown Forces

12

Hang a 300 g mass (including the weight hanger) at the angle marking 150°.

13

Choose values for the magnitude and angle of the second mass and enter this value in Data Table 2 on the worksheet.

You should only use weights in 10 g increments. Values for F2 must be different from the ones used in Procedure A.

Think about symmetry when you choose the angle for F2.

15

Draw the force diagram for this setup in the space provided on the worksheet.

16

Complete Data Table 2 and determine the magnitude and angle for F3 needed to produce equilibrium; i.e., to bring the ring to the center of the force table.

17

Now hang the two chosen masses at the chosen angles.

Adjust one or both of these masses as well as their angles, if necessary, so that the ring is centered on the force table. Enter these values on the worksheet.

18

Compute the percent difference between the chosen values and the experimental values for the magnitude of the two forces and record these on the worksheet.

19

Compute the percent difference between the chosen values and the experimental values for the angles of the two forces and record these on the worksheet.

Checkpoint 2:

Ask your TA to check your diagram, calculations and the set-up on the Force Table.

Ask your TA to check your diagram, calculations and the set-up on the Force Table.